Brewing up revenue: A nonprofit develops an income stream

Published in Indian Country Today in 2005. For more on topics like this, see my book, American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle....

Montreal, Quebec — Five years ago, Avataq Cultural Institute was looking for ways to bolster its bank account and better support its programs for the Inuit of Nunavik, the Arctic region of Quebec. “We’re a nonprofit, and that means we do a lot of fundraising,” explained communications director Taqralik Partridge, Inuk. “So in 2000, we formed a subsidiary, the Avataq Corporation, to develop ways to be more self-sustaining.”

Montreal, Quebec — Five years ago, Avataq Cultural Institute was looking for ways to bolster its bank account and better support its programs for the Inuit of Nunavik, the Arctic region of Quebec. “We’re a nonprofit, and that means we do a lot of fundraising,” explained communications director Taqralik Partridge, Inuk. “So in 2000, we formed a subsidiary, the Avataq Corporation, to develop ways to be more self-sustaining.”

The subsidiary surveyed resources in Nunavik and concocted a project that would create seasonal jobs for women, sustain traditional knowledge, and provide its parent organization with an income stream. The main ingredients? Crowberries, bearberries, and other plants that Inuit women have been picking for millennia during the Arctic summer.

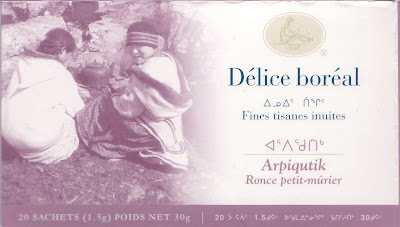

Tastings in Nunavik and at Trans-Herbes, a major Montreal-area processor of herbal teas, married not just plants, but sensibilities, as age-old customs and modern taste merged to produce five strikingly different blends — ranging from the cloudberry-based mix, with its rich butterscotch notes, to the floral mintiness of the ground-juniper infusion. Launched in 2002 under the name Northern Delights, the teas are sold nearly 1,000 health food stores across Canada, with sales of well over Canadian $100,000 a year.

Avataq Cultural Institute (an avataq is a harpoon fitted with a sealskin float) works to sustain Inuit culture from offices in Inukjuak and Montreal. The organization was founded 25 years ago by the Nunavik Inuit Elders Conference.

Partridge explained her community’s sense of urgency in regard to cultural-preservation issues: “Contact in the Arctic was very recent: from the 1870s in some areas to as late as the 1950s in others. In Nunavik, Inuttitut is the first language for ninety percent of the people — one of the highest uses of an original language in North America — and the schools use it exclusively up to grade three. Nevertheless, the advent of new media and the Internet has threatened both language and traditions.” Innovative projects like the tea business are especially valuable, in that they provide both jobs and a way to sustain the elders’ knowledge.

The cultural services that the subsidiary and its tea project support include supervision of all archaeological work in the region; partnerships with other cultural organizations, such as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.; grants for performing and visual artists; and publication in three languages (Inuttitut, English, and French) of magazines, books, and monographs. The group has issued elders’ memoirs, studies of traditional food and medicine for the region’s public-health board, and a collection of stories for children. Long-term plans include finding a permanent home for an important historical collection of arts, crafts, and everyday objects returned to the Inuit by the Canadian federal government.

The organization’s general director, Suzanne Beaubien, runs the tea project, which got underway following an environmental impact study and the creation of a harvesting manual. “We hired a botanist to go out on the land with the elders — the women who have the knowledge of the plants,” said Beaubien. “They defined the correct parts to pick, how much to take, when, and so on.” The harvested plants were dried on racks in a large tent in Nunavik, then shipped to Trans-Herbes to be placed in tea bags and either cellophane-wrapped cardboard boxes or wooden gift boxes.

Though the plants have never been sprayed or fertilized, they are not certified organic because there are no accreditation processes for tundra vegetation. So far, this has not been an impediment to sales. “People go for the full-bodied flavor,” explained Beaubien. “Even men like them. Women tell us that their husbands, who don’t ordinarily drink herbal teas, enjoy ours.”

However, she and her colleagues are taking a second look at the packaging. “Positioning — figuring out what people will notice and pick up at the store — is both difficult and very important,” said Partridge.

The current boxes and bags are in discreet natural-looking colors. They may be too discreet, according to Beaubien: “At Avataq, we put the accent on quality, whether we’re publishing a book or putting together an exhibition. When you see our product in a museum shop or an upscale boutique, it looks wonderful. However, at a health food store, among many competing teas, our packages can get lost. Perhaps a minor change in color will make them more noticeable.”

Meanwhile, Avataq markets the existing Northern Delights line via trade shows and in-store promotions. “We like to develop relationships with customers,” said Beaubien. “For the next twenty weeks, we’ll be doing four-hour tastings twice a week in health-food stores around Quebec.” She’s also looking into the permissions and certifications needed to export the product to the United States and Europe.

Another item on the agenda is construction of a permanent drying facility in Nunavik, which will allow residents to start related businesses. People in the region have already fielded ideas for selling dried mushrooms and berries.

Going forward, Avataq Corporation will focus on growing its already-successful tea business rather than on developing additional enterprises. Other ideas that came up during its original research, including aromatherapy and therapeutic products, will take a back seat. “All that may come,” said Beaubien. “However, since it’s easier to expand an existing operation than to start a new one, we’ll stick with improving the tea project for now.”

Text c. Stephanie Woodard; photograph courtesy Avataq.

Text c. Stephanie Woodard; photograph courtesy Avataq.