Going home: Navajo ballet star takes a new documentary to Dinétah and the world

Published in Indian Country Today in 2008. For more on topics like this, see my book, American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle....

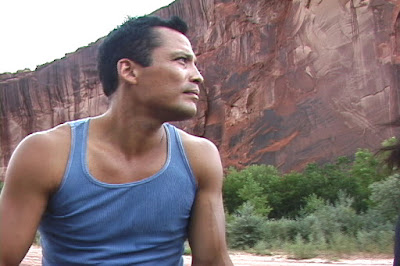

New York City, N.Y. — Respect, caring and sharing, the pillars of all Native communities, are underlying themes of Jock Soto’s life and of Water Flowing Together, a new film chronicling his story by Gwendolyn Cates. One of the greatest dancers of his generation, Soto, who’s Navajo on his mother’s side and Puerto Rican on his father’s, recently retired from the New York City Ballet at age 40. Presently him as sure-footedly as he supported the many ballerinas he partnered in his 24-year career, Cates follows him as he rehearses for his farewell performance, contemplates his future and travels to the Navajo reservation and Puerto Rico to reconnect with his heritage. (For photographs and a trailer, see www.waterflowingtogether.com.)

Soto, who is gay, told Indian Country Today that he asked Cates to make the film as an homage to his parents as well as to encourage closeted gays to come out. For Cates, whose 2001 book, Indian Country, is a major work of photojournalism, the project was “a tribute to Jock, his family and the Navajo people, to whom I am grateful for a lifelong education.” The two have shown the documentary at prestigious film festivals and on the Navajo Nation.

“Reactions at Window Rock were so heartfelt,” Soto said. “It meant a lot to me. The message? We can do anything.” Future showings of the award-winning movie, which is named after Soto’s Navajo clan, include National Museum of the American Indian on November 27, 2007, Santa Fe Film Festival on November 29, 2007, and PBS Independent Lens on April 8, 2008.

In archival footage, Cates introduces Soto as a boy, who lives on his own in New York City from age 14 to follow a dream he conceived at five, when he saw a ballet on The Ed Sullivan Show. In voice-over narration, Soto describes struggling to find an apartment and subsisting on cans of tuna shared with roommates. We also see him grinning happily as he dances all day at the New York City Ballet’s school and sneaks into the theater at night to watch the company perform.

Bursting with youthful energy, Soto is seen scampering through impossibly difficult steps and, at age 16, is asked to join the company by its revered founder, George Balanchine. Almost immediately, Soto begins to work closely with great ballerinas and choreographers, including Peter Martins, who took over the group’s directorship after Balanchine’s death in 1983.

Soto’s first important partner was ballerina Heather Watts, who became a dear friend. The two cooked feasts for friends and family, creating a sense of community that’s rare for dancers, who are caught up in their art from morning until late at night. The duo’s passion for feeding others eventually resulted in a cookbook, Our Meals, published in 1997.

Soto was not the first Native American to excel in ballet. Prima ballerina Maria Tallchief, Osage, was a star of the New York City Ballet during the 1940s and 1950s and went on to run the Chicago City Ballet. Her sister, Marjorie Tallchief, Osage, was also a ballerina, as were Rosella Hightower, Choctaw; Yvonne Chouteau, Cherokee; and Moscelyne Larkin, Shawnee. In accomplishing this, all lived far from their homelands.

Yet, Soto’s mother says in the film, heritage is an enduring aspect of identity —even when the individual doesn’t comprehend the tradition. “Much of Jock’s magic comes from an inheritance he doesn’t understand,” says Mama Jo. An aunt demurs, saying, “He’s a New Yorker; people out there know who he really is.” In her view, it takes a village to know who you are, and in reaching out to Navajos and other Native people, Soto is carefully recreating those ties.

After Watts retired in 1995, Soto danced frequently with ballerina Wendy Whelan (shown together in two photos here). In rehearsal and performance footage of Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain, made for the duo, Cates’s film reveals why Soto’s dancing was invariably called both masculine and spiritual. It’s not simply maleness his admirers refer to, just as Whelan’s dancing is not just about being female. By presenting masculinity as power rooted in the physical world, he releases her — literally by lifting her in daring airborne flourishes, but also metaphorically — to portray realms of the soul.

Soto and Whelan don’t act out this process. They experience it. Whelan tells Cates that her collaboration with Soto is a melding of their spirits. He calls dancing with Whelan “an out-of-body experience … we’re in heaven.”

Back on earth, 24 years of hoisting ballerinas has taken its toll. “I hurt,” Soto says, cataloging his injuries for Cates’s camera. He plans to start culinary school the day after his farewell performance in June 2005, in part to stave off the identity loss dancers suffer after their inevitably all-too-short careers end. After his last appearance — a sold-out gala attended by thousands of fans, as well as relatives from Dinétah — he is seen backstage embracing his parents.

“I marvel at the way he’s turned out,” says his mother. Soto’s dad, Papa Joe, quips, “He used to watch Mama Jo and me dance merengue. That’s where he picked all that stuff up.”

“My dad thinks he’s the star of the film,” Soto joked in an interview with Indian Country Today.

Cates intersperses the film’s credits with shots of Soto in cooking school. “I graduated,” he exults, holding up his diploma. With a boyish grin, he’s off on another adventure, teaching ballet and planning to open a catering company and restaurant.

Today, his life has a new, easier rhythm. “I have my nights free,” Soto reported. “My partner and I cook for each other and watch Jeopardy.” In our life journey, we circle back and move forward repeatedly, spiraling upward to greater understanding — with an occasional well-deserved breather.

Text c. Stephanie Woodard; images c. Gwendolyn Cates.

Text c. Stephanie Woodard; images c. Gwendolyn Cates.