Tribes take on youth suicide with skits, mustangs and ceremonies

This article appeared in Indian Country Today in 2013. For more on topics like this, see my book, American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle....

On the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, youngsters perform skits aimed at

lowering their tribe’s youth-suicide rate. Playing with mustangs helps prevent self-harm

among the children of the Gila River Indian Community. On the Standing Rock

Sioux Reservation, tribal members who’ve lost family to suicide heal by

grieving together. In each of these three communities, youngsters kill themselves at a rate

at least triple the United States average.

“American Indian and Alaska Native

youth have the highest suicide rates in the country,” said Richard

McKeon, chief of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s suicide-prevention

branch. To help quell this epidemic, Native groups received about a third of

the agency’s recent round of grants. “We want to help as many as tribes as

possible reduce risk factors, such as substance abuse and depression.”

“American Indian and Alaska Native

youth have the highest suicide rates in the country,” said Richard

McKeon, chief of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s suicide-prevention

branch. To help quell this epidemic, Native groups received about a third of

the agency’s recent round of grants. “We want to help as many as tribes as

possible reduce risk factors, such as substance abuse and depression.”

With the grants, the tribes will

also bolster what scientists call protective factors. “For Native people, that

means connecting with culture, an extremely important asset, as well as family

and community,” said McKeon.

Throughout Indian Country, even very young children are included in

prevention events and activities. “On the Pine Ridge Indian

Reservation, we can start talking about suicide when kids are in pre-school,”

said Yvonne “Tiny” DeCory, staffer for the Sweetgrass Project, a tribal suicide

prevention program.

How do you broach such a subject with a five-year-old? “Our

kindergarteners can tell you about how daddy hung himself,” DeCory responded.

“They go to wakes and funerals. Suicide has become ‘normal’ to them.” So, she

and other mentors on Pine Ridge face the crisis square on, with frank words and

compassion.

DeCory’s description of the work at Pine Ridge could describe many

tribes’ efforts: “We have to end the silence and walk out of the darkness

together.” Here are ways tribes are helping their kids feel connected and valued.

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe: Healing

together

“Forever is a long, long time / So I will forever remember you.” The sweet

refrain floated over a November grieving ceremony on the Standing Rock Sioux

reservation. About 75 people had gathered for a meal and remembrance in a

meeting room of the tribe’s hotel in Mobridge, South Dakota. Youth suicide at

Standing Rock has been marked by not just high rates, but devastating clusters

of deaths. Seven youngsters in one tiny community killed themselves in six

weeks in 2009. Some clusters have been even higher, and others have been

included dozens of attempts, in addition to the deaths.

The singer at the gathering composed the plaint for relatives lost to

suicide—a son, a nephew, a niece, cousins and uncles, deaths stretching back to

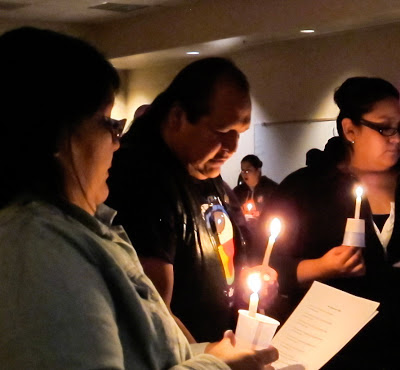

the 1970s, she said. Veronica Iron Thunder, shown here at left in photo, who survived her own suicide

attempts, sang a traditional Lakota song intended to restore damaged spirits.

A third woman said she was finally able to accept her son’s death by

suicide—though she said, as do many survivors, that she still couldn’t

understand why it had happened. “After 15 years of mourning, I took flowers to

his grave and said, ‘goodbye, son.’”

“That was so important for others to hear,” said tribal wellness program

director Arleata Snell. Some Standing Rock families have been overwhelmed by

grief for years, unable to move on, she said. “Now, maybe they’ll see it is

possible to heal.”

In a slideshow, the beautiful, smiling faces of those lost to suicide

slipped across the screen. Almost all were in their teens and twenties. They

radiated hope. But they were also heartbreaking. A small indigenous community

had lost so many of those who should be leading it into the future.

“We’re in this together, from prevention to healing,” said Snell. “We’ve

trained youth how to recognize and report signs of suicide in their peers, and

adults know the suicide-prevention protocol ASIST. Schools, health service,

spiritual people—everyone here is helping stop youth suicide.”

These days, Standing Rock is experiencing an uneasy calm, with generally

lower numbers, said Snell. “If people are in crisis, they know who to call,

whether it’s our program or the national hotline—1-800-SAFE-TALK.” She also worked

with the national call center to route calls from Standing Rock to a local counselor.

Normally, Snell said, callers from across the nation get a professional

counselor who may be anywhere in the country. But now, Standing Rock callers

get a local person who understands how hard it is for people to get themselves

to help on big reservations, with their long distances, great poverty and

little access to transport.

Snell and her staff of four are the wellness program’s eyes and ears in

Standing Rock’s scattered communities. They respond immediately to suicide

ideations (plans) or attempts, contacting parents if minors are involved and

arranging transport to counseling or an emergency room.

Ira Taken Alive, chair of the Standing Rock Sioux Suicide Task Force

called his tribe’s response to youth suicide “all hands on deck.” The task

force meets monthly. Members have discussed the little-understood fact that suicides

occur mostly in spring or fall. “It may be seasonal affective disorder and a

response to changing amounts of sunlight, though no one really knows,” said

Taken Alive.

Ira Taken Alive, chair of the Standing Rock Sioux Suicide Task Force

called his tribe’s response to youth suicide “all hands on deck.” The task

force meets monthly. Members have discussed the little-understood fact that suicides

occur mostly in spring or fall. “It may be seasonal affective disorder and a

response to changing amounts of sunlight, though no one really knows,” said

Taken Alive.

They’ve talked about substance abuse. “One thing is sure,” Taken Alive

said. “In 98 percent of attempts and completions here, alcohol or drugs were

involved. We need to get ahead of the substance-abuse issue, to be proactive,

not reactive.”

The grieving families ate together, then entertainer and motivational speaker

Mylo Redwater Smith, shown in photos above (at left) and below, closed the event. A 25-year-old Dakota from Crow Creek

Sioux Tribe, he lightened the atmosphere with jokes and skits. Then he launched into a

fast-moving analysis of how generations of attempts to assimilate tribal people

have meant loss upon loss—of homeland, language, cultural practices, the

ability to support their families, good health and more. As a result, Natives have taken up destructive behaviors—suicide, alcoholism,

domestic violence, drug use and other dysfunctions—and made them their “new

normal,” Smith said.

“All the negative things add up for our children,” Smith said. “They say

to themselves, ‘I’m alone. It’s too hard.’ They may give up.” To help

youngsters overcome what he called the “reservation mentality,” they have to

connect with their culture, according to Smith. “Take them to the sweat. Teach

them to pray. In ceremony, I found who I was as a young Dakota man. That saved

my life.”

“All the negative things add up for our children,” Smith said. “They say

to themselves, ‘I’m alone. It’s too hard.’ They may give up.” To help

youngsters overcome what he called the “reservation mentality,” they have to

connect with their culture, according to Smith. “Take them to the sweat. Teach

them to pray. In ceremony, I found who I was as a young Dakota man. That saved

my life.”

Smith was optimistic. “It’s hard to be Indian,” he said. “But we as a

people are defining our problems and looking for solutions. This is a time of

healing.”

Gerald Iron Shield closed the day with a prayer and traditional Lakota

song. “We can become strong again,” he said.

Gila River Indian Community:

Mustang sallies

Herds of wild horses still roam free in the Gila River Indian

Community’s stretch of the Sonoran Desert, south of Phoenix, Arizona. Mustangs

are also important to a tribal youth suicide-prevention and life-skills program,

Kahv’Yoo (“horse”) Spirit, run by

horseman Andy Miritello, with therapist Shawn Rodrigues.

The kids don’t hop aboard wild animals and try to ride them, cautioned

Miritello. The program uses a ground-based method, EAGALA (Equine Assisted

Psychotherapy and Equine Assisted Learning), developed by the international

nonprofit of the same name. Everything happens on the ground, with kids on

foot, grooming and interacting with the animals, which include domesticated

horses. This eliminates the issues of power and control over the animal that

are essential to riding a horse, said Miritello.

Instead, people and animals are equals in a friendly, low-key herd

sharing a corral. This was apparent to Gila River youth, who used human imagery

to describe the horses. “They show emotions like people do,” said teen participant

Jacquelyn Osife.

Mustangs bring a special element to the mix. “They’re more alert and

sensitive than domesticated horses,” Miritello said. “They have to be to

survive. It’s literally in a mustang’s DNA. They also project a powerful sense

of life that inspires the children, who are from a horse culture.”

Some lessons involve observing the animals’ responses and figuring out

if they relate to other aspects of your life, said Julie Jimenez, prevention

administrator for the behavioral health department. “A child might observe,

‘that horse just walked away from me,’ then reveal that kids at school do the

same thing. The therapist might ask, ‘How did you approach the horse (or the

kids)?’ A conversation will develop from there.”

Handling a big animal is empowering, said Miritello. He described a girl

who became increasingly confident as she haltered a horse and led it around the

arena with a rope. For the next step, she removed the rope and circled the

corral, with the horse following freely, like an oversized friendly dog. “She

was thrilled,” he recalled.

The children’s achievements give them optimism and help them stay away

from life-threatening behaviors, including drugs, alcohol and self-harm,

according to Miritello. “They connect to self, peers, community and culture,”

he said. Teachers have reported better school attendance and behavior among

program participants.

All tribal youth aged 5 to 24 are eligible to participate in the

once-a-week, 8-week sessions, which can be repeated. Kahv’Yoo Spirit is among

several Gila River suicide-prevention initiatives supported by state funding

and the National Indian Health Board, said Jimenez. These include a summer

culture camp and a coalition of providers and community members who get the

prevention message out with block parties, a skateboarding competition and

other events. Meanwhile, 400 adults have learned a protocol for recognizing and

reporting signs of suicide.

Teen Kahv’Yoo Spirit participant Rodrigo Castellon said working with

horses was transforming. “You see the world with different, more positive

eyes.”

Oglala Sioux Tribe: Serious fun

Night had fallen, and 32 teens living in Pine Ridge High School’s dorm,

in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, were seated around small tables in a common room.

Each group was quietly discussing things that could happen to a

person—learning a friend has been abused, coming home from school to find

auntie drunk, flunking a test, getting ketchup on a prom dress. They ranked

them from least to most serious.

Night had fallen, and 32 teens living in Pine Ridge High School’s dorm,

in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, were seated around small tables in a common room.

Each group was quietly discussing things that could happen to a

person—learning a friend has been abused, coming home from school to find

auntie drunk, flunking a test, getting ketchup on a prom dress. They ranked

them from least to most serious.

This was one of the problem-solving lessons the teens will complete

under the American Indian Life Skills Development curriculum, a

suicide-prevention syllabus for Native youth. Charismatic, high-energy Tiny DeCory, shown here, teaches the lessons through the

tribe’s Sweetgrass Project, run by Lisa Schrader-Dillon. The program just

received its second Garrett Lee Smith three-year grant. In the curriculum’s

original incarnation—as Zuni Life Skills Development—it eliminated youth

suicide at the pueblo for the 15 years it was in effect. It’s on SAMHSA’s list

of evidence-based (scientifically tested) practices.

As the Pine Ridge teens ranked each list, they announced their results.

Generally the groups agreed among each other, until four boys declared facial

blemishes to be life’s greatest disaster, to shrieks of laughter from the other

kids.

“The issues are serious, but the way Tiny presents the material, the

students don’t think of it as a ‘curriculum’,” said dorm manager Allie Bad

Heart Bull, shown here. Bad Heart Bull radiates quiet capability and offers meditation and other

alternative healing practices to dorm residents.

“The issues are serious, but the way Tiny presents the material, the

students don’t think of it as a ‘curriculum’,” said dorm manager Allie Bad

Heart Bull, shown here. Bad Heart Bull radiates quiet capability and offers meditation and other

alternative healing practices to dorm residents.

“We’ve seen changes in behavior already,” said DeCory. “In the lessons,

the teens have talked about solutions to all kinds of problems. They’ve become

more communicative and seem stronger and happier.” Children on Pine Ridge have

the capacity for great resilience, she said. “We’re working to make this their

turnaround moment.”

The next day, DeCory’s youth theater group, B.E.A.R., performed for a

packed crowd at another reservation high school, shown here. B.E.A.R is also under the Sweetgrass

umbrella; the initials stand for Be Excited About Reading, while the name

refers to cultural beliefs about bears’ wisdom and strength. The group hands

out books and encourages literacy at its approximately four monthly shows on

and off the reservation.

“We started out to improve test scores,” said DeCory. It soon became

apparent that B.E.A.R.’s youth audiences also wanted information about serious

issues they face. The group’s kid-developed skits don’t pull any punches. They

deal with teen pregnancy, coping with alcoholic relatives, suicide and other

problems youngsters in their audiences face. They provide information on where

to go for help.

“We started out to improve test scores,” said DeCory. It soon became

apparent that B.E.A.R.’s youth audiences also wanted information about serious

issues they face. The group’s kid-developed skits don’t pull any punches. They

deal with teen pregnancy, coping with alcoholic relatives, suicide and other

problems youngsters in their audiences face. They provide information on where

to go for help.

For its members, B.E.A.R. provides

the all-important, life-saving sense of connection. After Erin Miller’s mom saw

her perform, the two bonded powerfully. “We cried together,” said Erin, who’s

18. Shawn Keith, 23, has been with B.E.A.R. since he was a young

teen. “It means everything to me,” he said.

Text and photographs c. Stephanie Woodard, who wrote this story—part of a series on tribal efforts to prevent youth suicide—with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC’s Annenberg School of Journalism.