Made in the Shade: Reservation Tree Planting Takes Off

This article appeared in Indian Country Today in 2013. For more on topics like this, see my book, American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle....

“Trees offer food, shelter,

shade and privacy; they control erosion and air pollution, and they’re

beautiful,” said Ryhal Rowland, extension agent for the Northern Cheyenne

Extension Service, in Lame Deer, Montana. The service was finishing up its

annual spring tree and shrub extravaganza, during which it sold 2,700 plants

for $1 each. “Most

people bought 10 to 20 seedlings, and we provided them with planting and care

instructions—siting, spacing, soil preparation, watering and so on,” said the

service’s administrative assistant Pamela Dahl. Lilacs have always been a

favorite with the older generation, Dahl said. “They’re still top sellers,

along with crabapple trees and chokecherry and juneberry bushes.”

“Trees offer food, shelter,

shade and privacy; they control erosion and air pollution, and they’re

beautiful,” said Ryhal Rowland, extension agent for the Northern Cheyenne

Extension Service, in Lame Deer, Montana. The service was finishing up its

annual spring tree and shrub extravaganza, during which it sold 2,700 plants

for $1 each. “Most

people bought 10 to 20 seedlings, and we provided them with planting and care

instructions—siting, spacing, soil preparation, watering and so on,” said the

service’s administrative assistant Pamela Dahl. Lilacs have always been a

favorite with the older generation, Dahl said. “They’re still top sellers,

along with crabapple trees and chokecherry and juneberry bushes.”

After years of intensive planting of flowering and fruiting plants, the Northern Cheyenne homeland is covered in spring and summer with clouds of fragrant lavender, purple, pink and white blossoms. Several miles from Lame Deer, an ornamental cherry tree presided over Patricia and Richard Rowland’s yard, which was bounded by hedges of mature lilacs and a grove of crabapple trees (shown here). Similar uplifting sights abounded—lyrical embellishments of the dramatic landscape of craggy mountains and broad green valleys.

After years of intensive planting of flowering and fruiting plants, the Northern Cheyenne homeland is covered in spring and summer with clouds of fragrant lavender, purple, pink and white blossoms. Several miles from Lame Deer, an ornamental cherry tree presided over Patricia and Richard Rowland’s yard, which was bounded by hedges of mature lilacs and a grove of crabapple trees (shown here). Similar uplifting sights abounded—lyrical embellishments of the dramatic landscape of craggy mountains and broad green valleys.

As warm weather arrives across the country, extension services, tribal forestry departments and funders such as First Nations Development Institute and the Fruit Tree Planting Foundation are helping tribal members put in trees of all types. According to First Nations senior program officer Raymond Foxworth, Navajo, the group has assisted new or established orchards for the Oneidas of Wisconsin, the Hopi and Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College. “Our grantees distribute fruit and information about healthy eating within their communities, as well as bring produce to market,” Foxworth said.

For two years, North Dakota’s agriculture department has funded improvements to United Tribes Technical College’s fruit orchard, which supplies the cafeteria and is part of a research and demonstration garden in Bismarck. “Our community-orchards grants support education, beautification and getting the fruits and berries right into local hands,” said Jamie Good, the department’s local foods specialist. “This boosts both health and community spirit.”

For two years, North Dakota’s agriculture department has funded improvements to United Tribes Technical College’s fruit orchard, which supplies the cafeteria and is part of a research and demonstration garden in Bismarck. “Our community-orchards grants support education, beautification and getting the fruits and berries right into local hands,” said Jamie Good, the department’s local foods specialist. “This boosts both health and community spirit.”

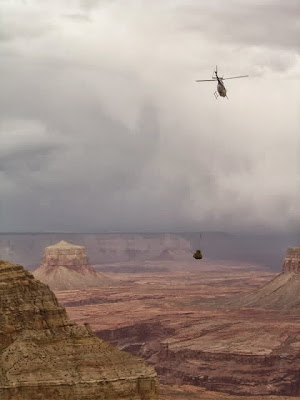

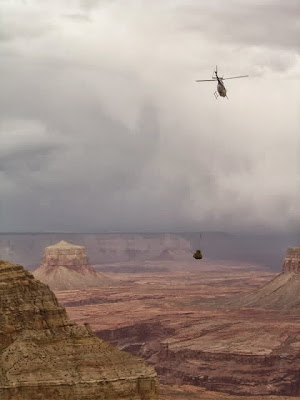

Through its Trees for Tribes program, the Fruit Tree Planting Foundation has installed orchards on dozens of tribal homelands and even used helicopters to airlift plants into the Havasupai Tribe’s remote village at the base of the Grand Canyon (shown here). The foundation collaborates with local groups and individuals, according to director Cem Akin. “That way, advocates for the orchards remain as the trees mature,” said Akin.

On Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, Akin’s foundation recently established five orchards. Under the direction of arborist Rico Montenegro, tribal members planted phalanxes of young trees at schools and community organizations. The lead local partner was Earth Tipi—a sustainable-living nonprofit in Manderson and the site of the fruit-tree foundation’s first Pine Ridge project, in 2011.

Robert Brave Heart, an official at Red Cloud Indian School, one of the five new sites, called Pine Ridge a “food desert” and said the trees would become a critical community resource. “None of us will sell the fruit,” explained Earth Tipi director Shannon Freed, but rather will manage pick-your-own operations, a requirement of the foundation.

In Lame Deer, Rowland, who is Northern Cheyenne, checked in with Rhonda Sankey, as she mixed peat moss and soil and got ready to plant 10 newly purchased blue spruces (both are shown here). Sankey eyed a row of holes in her lawn: “My kids helped dig the row. I guess it’s straight!”

While individuals like Sankey were enhancing their homesites, the tribal forestry department was replanting ponderosa pines on the thousands of reservation acres burnt by last year’s forest fires, said Rowland. “The fires were horrendous, terrifying, the worst in living memory. It’ll take years to replant.” At 30 cents per tree, the springtime reforestation job is a good gig for tribal members, who can typically plant 1,000 trees a day, earning $300, she said: “For some, it’s the only income they’ll have all year.”

Looking at the hills surrounding her yard, Sankey, who is Blackfeet, recalled the damage. “The fire came just to the top of them. This side looks normal, but the other side is completely charred.”

Looking at the hills surrounding her yard, Sankey, who is Blackfeet, recalled the damage. “The fire came just to the top of them. This side looks normal, but the other side is completely charred.”

Sankey lifted the bare-root spruces from a basket of peat moss, tucked them into their new homes and surrounded each with a wire cage to protect it from marauding animals. She and Rowland shared gardeners’ war stories of cats and dogs gnawing on small trees, goats making a meal of them and horses simply yanking them out of the ground. “My goats ate the lilacs I put in last year,” Sankey recalled ruefully. (Sankey’s 10-year-old daughter, Nonee White, shows off her treehouse in the photo here.)

The spruces will do well, not least because the area’s soil is so good. “A river once ran through here, so the soil is very rich,” explained Sankey. “These seedlings will grow nearly a foot a year and within five years will screen the house from the road.”

On the Crow Creek Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, a brand-new orchard is taking root with support from First Nations Development Initiative. In April, a hardy group gathered in Fort Thompson just after the season’s last big snowstorm to plant 200 trees and 70-plus shrubs, including traditional favorites such as wild plums, chokecherries and buffalo berries. They went in on land provided by nearby Christ Episcopal Church.

On the Crow Creek Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, a brand-new orchard is taking root with support from First Nations Development Initiative. In April, a hardy group gathered in Fort Thompson just after the season’s last big snowstorm to plant 200 trees and 70-plus shrubs, including traditional favorites such as wild plums, chokecherries and buffalo berries. They went in on land provided by nearby Christ Episcopal Church.

The tree enthusiasts donned parkas and boots to dig and plant, with tribal chairman Brandon Sazue (at left in photo here) leading the way. “Putting in the first tree was an honor for me,” said Sazue. “It was a cold, foggy day, but everyone was out there. It showed lots of dedication, and I thanked them for the job they were doing.”

That spring day may have been surprisingly chilly and wet, but the snowfall got the reservation out of drought status—just barely, but nevertheless a welcome change from the past several parched years, said Billy Joe Sazue, coordinator of the gardens program, part of local community development group Hunkpati Inc. According to Sazue, the trees will bear fruit in three to five years, with the berry bushes probably producing sooner than that. “It’s all about healthy food and eating,” he said.

Much planning—from researching suitable plant varieties to designing the irrigation system—preceded planting day, said Hunkpati’s new director, Corrie Ann Campbell (shown with Billy Joe Sazue in the brand-new orchard). Joining Hunkpati and First Nations in the preparations were tribal members, the tribal council, Diamond Willow Ministries, additional churches, Boys and Girls Club of Three Districts, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Service and nearby Lower Brule Sioux Tribe’s wildlife department. “We were blessed to have so many great partners,” said Krystal Langholz, former director of Hunkpati, on whose watch the orchard was conceived and planted.

Much planning—from researching suitable plant varieties to designing the irrigation system—preceded planting day, said Hunkpati’s new director, Corrie Ann Campbell (shown with Billy Joe Sazue in the brand-new orchard). Joining Hunkpati and First Nations in the preparations were tribal members, the tribal council, Diamond Willow Ministries, additional churches, Boys and Girls Club of Three Districts, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Service and nearby Lower Brule Sioux Tribe’s wildlife department. “We were blessed to have so many great partners,” said Krystal Langholz, former director of Hunkpati, on whose watch the orchard was conceived and planted.

Said Campbell: “The orchard is one of many positive changes in the way people at Crow Creek view nutrition, exercise and health.”

Trees provide everything from fruit to an opportunity to mobilize a community, according to Akin: “Their energy is healing. Trees do it all.”

“Trees offer food, shelter,

shade and privacy; they control erosion and air pollution, and they’re

beautiful,” said Ryhal Rowland, extension agent for the Northern Cheyenne

Extension Service, in Lame Deer, Montana. The service was finishing up its

annual spring tree and shrub extravaganza, during which it sold 2,700 plants

for $1 each. “Most

people bought 10 to 20 seedlings, and we provided them with planting and care

instructions—siting, spacing, soil preparation, watering and so on,” said the

service’s administrative assistant Pamela Dahl. Lilacs have always been a

favorite with the older generation, Dahl said. “They’re still top sellers,

along with crabapple trees and chokecherry and juneberry bushes.”

“Trees offer food, shelter,

shade and privacy; they control erosion and air pollution, and they’re

beautiful,” said Ryhal Rowland, extension agent for the Northern Cheyenne

Extension Service, in Lame Deer, Montana. The service was finishing up its

annual spring tree and shrub extravaganza, during which it sold 2,700 plants

for $1 each. “Most

people bought 10 to 20 seedlings, and we provided them with planting and care

instructions—siting, spacing, soil preparation, watering and so on,” said the

service’s administrative assistant Pamela Dahl. Lilacs have always been a

favorite with the older generation, Dahl said. “They’re still top sellers,

along with crabapple trees and chokecherry and juneberry bushes.” After years of intensive planting of flowering and fruiting plants, the Northern Cheyenne homeland is covered in spring and summer with clouds of fragrant lavender, purple, pink and white blossoms. Several miles from Lame Deer, an ornamental cherry tree presided over Patricia and Richard Rowland’s yard, which was bounded by hedges of mature lilacs and a grove of crabapple trees (shown here). Similar uplifting sights abounded—lyrical embellishments of the dramatic landscape of craggy mountains and broad green valleys.

After years of intensive planting of flowering and fruiting plants, the Northern Cheyenne homeland is covered in spring and summer with clouds of fragrant lavender, purple, pink and white blossoms. Several miles from Lame Deer, an ornamental cherry tree presided over Patricia and Richard Rowland’s yard, which was bounded by hedges of mature lilacs and a grove of crabapple trees (shown here). Similar uplifting sights abounded—lyrical embellishments of the dramatic landscape of craggy mountains and broad green valleys.As warm weather arrives across the country, extension services, tribal forestry departments and funders such as First Nations Development Institute and the Fruit Tree Planting Foundation are helping tribal members put in trees of all types. According to First Nations senior program officer Raymond Foxworth, Navajo, the group has assisted new or established orchards for the Oneidas of Wisconsin, the Hopi and Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College. “Our grantees distribute fruit and information about healthy eating within their communities, as well as bring produce to market,” Foxworth said.

For two years, North Dakota’s agriculture department has funded improvements to United Tribes Technical College’s fruit orchard, which supplies the cafeteria and is part of a research and demonstration garden in Bismarck. “Our community-orchards grants support education, beautification and getting the fruits and berries right into local hands,” said Jamie Good, the department’s local foods specialist. “This boosts both health and community spirit.”

For two years, North Dakota’s agriculture department has funded improvements to United Tribes Technical College’s fruit orchard, which supplies the cafeteria and is part of a research and demonstration garden in Bismarck. “Our community-orchards grants support education, beautification and getting the fruits and berries right into local hands,” said Jamie Good, the department’s local foods specialist. “This boosts both health and community spirit.”Through its Trees for Tribes program, the Fruit Tree Planting Foundation has installed orchards on dozens of tribal homelands and even used helicopters to airlift plants into the Havasupai Tribe’s remote village at the base of the Grand Canyon (shown here). The foundation collaborates with local groups and individuals, according to director Cem Akin. “That way, advocates for the orchards remain as the trees mature,” said Akin.

On Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, Akin’s foundation recently established five orchards. Under the direction of arborist Rico Montenegro, tribal members planted phalanxes of young trees at schools and community organizations. The lead local partner was Earth Tipi—a sustainable-living nonprofit in Manderson and the site of the fruit-tree foundation’s first Pine Ridge project, in 2011.

Robert Brave Heart, an official at Red Cloud Indian School, one of the five new sites, called Pine Ridge a “food desert” and said the trees would become a critical community resource. “None of us will sell the fruit,” explained Earth Tipi director Shannon Freed, but rather will manage pick-your-own operations, a requirement of the foundation.

In Lame Deer, Rowland, who is Northern Cheyenne, checked in with Rhonda Sankey, as she mixed peat moss and soil and got ready to plant 10 newly purchased blue spruces (both are shown here). Sankey eyed a row of holes in her lawn: “My kids helped dig the row. I guess it’s straight!”

While individuals like Sankey were enhancing their homesites, the tribal forestry department was replanting ponderosa pines on the thousands of reservation acres burnt by last year’s forest fires, said Rowland. “The fires were horrendous, terrifying, the worst in living memory. It’ll take years to replant.” At 30 cents per tree, the springtime reforestation job is a good gig for tribal members, who can typically plant 1,000 trees a day, earning $300, she said: “For some, it’s the only income they’ll have all year.”

Looking at the hills surrounding her yard, Sankey, who is Blackfeet, recalled the damage. “The fire came just to the top of them. This side looks normal, but the other side is completely charred.”

Looking at the hills surrounding her yard, Sankey, who is Blackfeet, recalled the damage. “The fire came just to the top of them. This side looks normal, but the other side is completely charred.”Sankey lifted the bare-root spruces from a basket of peat moss, tucked them into their new homes and surrounded each with a wire cage to protect it from marauding animals. She and Rowland shared gardeners’ war stories of cats and dogs gnawing on small trees, goats making a meal of them and horses simply yanking them out of the ground. “My goats ate the lilacs I put in last year,” Sankey recalled ruefully. (Sankey’s 10-year-old daughter, Nonee White, shows off her treehouse in the photo here.)

The spruces will do well, not least because the area’s soil is so good. “A river once ran through here, so the soil is very rich,” explained Sankey. “These seedlings will grow nearly a foot a year and within five years will screen the house from the road.”

The tree enthusiasts donned parkas and boots to dig and plant, with tribal chairman Brandon Sazue (at left in photo here) leading the way. “Putting in the first tree was an honor for me,” said Sazue. “It was a cold, foggy day, but everyone was out there. It showed lots of dedication, and I thanked them for the job they were doing.”

That spring day may have been surprisingly chilly and wet, but the snowfall got the reservation out of drought status—just barely, but nevertheless a welcome change from the past several parched years, said Billy Joe Sazue, coordinator of the gardens program, part of local community development group Hunkpati Inc. According to Sazue, the trees will bear fruit in three to five years, with the berry bushes probably producing sooner than that. “It’s all about healthy food and eating,” he said.

Much planning—from researching suitable plant varieties to designing the irrigation system—preceded planting day, said Hunkpati’s new director, Corrie Ann Campbell (shown with Billy Joe Sazue in the brand-new orchard). Joining Hunkpati and First Nations in the preparations were tribal members, the tribal council, Diamond Willow Ministries, additional churches, Boys and Girls Club of Three Districts, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Service and nearby Lower Brule Sioux Tribe’s wildlife department. “We were blessed to have so many great partners,” said Krystal Langholz, former director of Hunkpati, on whose watch the orchard was conceived and planted.

Much planning—from researching suitable plant varieties to designing the irrigation system—preceded planting day, said Hunkpati’s new director, Corrie Ann Campbell (shown with Billy Joe Sazue in the brand-new orchard). Joining Hunkpati and First Nations in the preparations were tribal members, the tribal council, Diamond Willow Ministries, additional churches, Boys and Girls Club of Three Districts, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Service and nearby Lower Brule Sioux Tribe’s wildlife department. “We were blessed to have so many great partners,” said Krystal Langholz, former director of Hunkpati, on whose watch the orchard was conceived and planted.Said Campbell: “The orchard is one of many positive changes in the way people at Crow Creek view nutrition, exercise and health.”

Trees provide everything from fruit to an opportunity to mobilize a community, according to Akin: “Their energy is healing. Trees do it all.”

Text and photographs c. Stephanie Woodard.